Author Archives: Hasan

الإبداع في الإبداع – خريف ٢٠١٩

زهراء يعقوب (٢٨١)

غصيت فيك يا (hairpin loop) شدفعك في

Mariam Ahmed Yousri (281)

* Once upon a time, an Adenine said “I want to marry U in RNA”

* How we reach other doesn’t matter. The beginning and the end are what really matters (the meaning of △)

* كل عقدة ولها حلال. وكل (Nucleic acid) وله (Polymerase)

* خالتي وخالتك واتفرقوا الخالات، وال (leading template strand) وال (lagging template strand) واتفرقوا ال (strands)

* إن سرقت اسرق جمل، وإن عشقت اعشق قمر، وإن عملت (mutation) اعمل (deletion)

سارة خالد العجمي (٢٨١)

ما اردى من المربوط إلا المفتلت وما اردى من (Rho independent termination) إلا (Rho dependent termination)

هاجر فالح الهاجري (٢٨١)

في حياتك لا تسمح لاحد يخرب سعادتك، خلك مثل (DNA Pol I) كل ما صادف (wrong nucleotide) طرده من طريقه

فاطمة صباح محمد (٢٨١)

غصيت فيك يا ماي شدفعك في، مثل ال (Hairpin loop) مع ال (RNA polymerase)

نور عدنان الصالح (٢٨١)

إذا ياكم الطارش صيدوه واذا ياكم (the correct nucleotide) صيدوه

سارة السريع (٢٨١)

لو جريت جري الوحوش غير رزقك ما تحوش

ولو ترجمت كل الحروف غير الجينوم ما تشوف

Hanan Mohammed Alshuraian (281)

لي طاح الجمل كثرت سكاكينه

ولي طاح ال (DNA) كثرت تطافيره (mutations)

Nouf Fawaz Alsulaiman (281)

Who thought it was a good idea to make the iPhone camera go through mitosis

مريم احمد شقير (٢٨١)

كلمة ورد غطاها بين ال (DNA) وال (RNA)

(RNA): عاوزه اخد نسخه من صفحة من كتابك

(DNA): اللي عاوزني يجيني انا مبروحش لحد

وضحة العازمي (٢٨١)

طنجرة ولقت غطاها مثل الجوانين والسيتوسين

ايام الهاجري (٢٨١)

لو جريت جري الوحوش غير (your genes) ما تحوش

Nice creative work by Mariam Alhadlaq

Nice artistic work by Fatima Jawad

Nice creative work

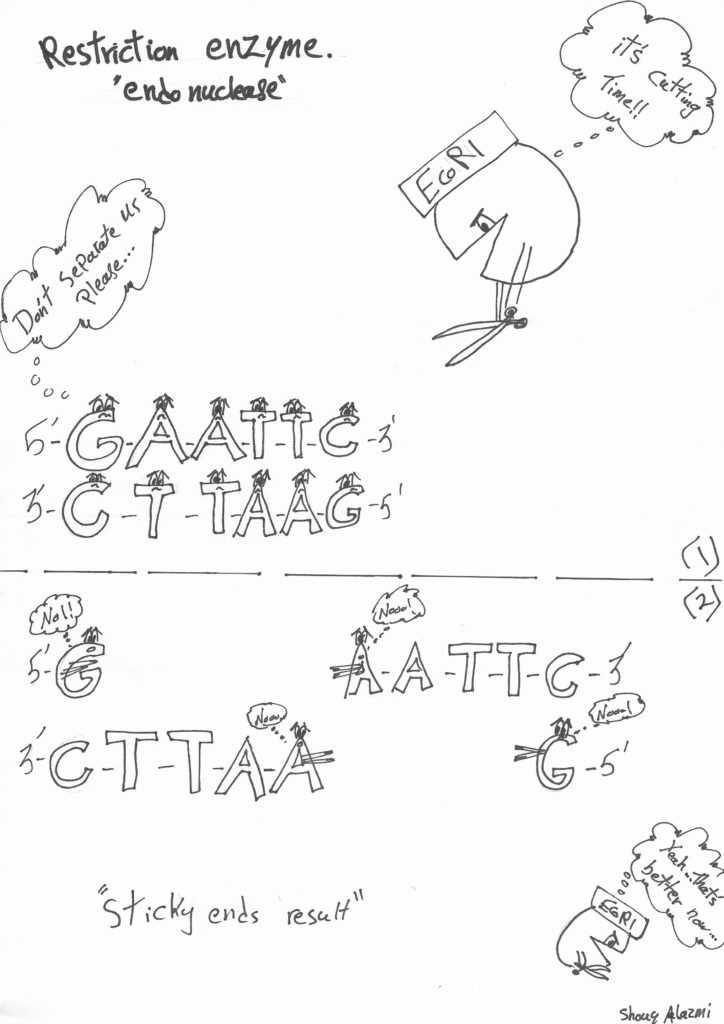

Shouq Alazmi (485)

Bashayer Jamal (485)

Shaikha Alshariafi (485)

Anfal Alsahaf (281)

Badreya Alnassar (281)

DNA Sequencing Arabic poem

Very nice poem by Zainab Ahmed from my Genomics class.

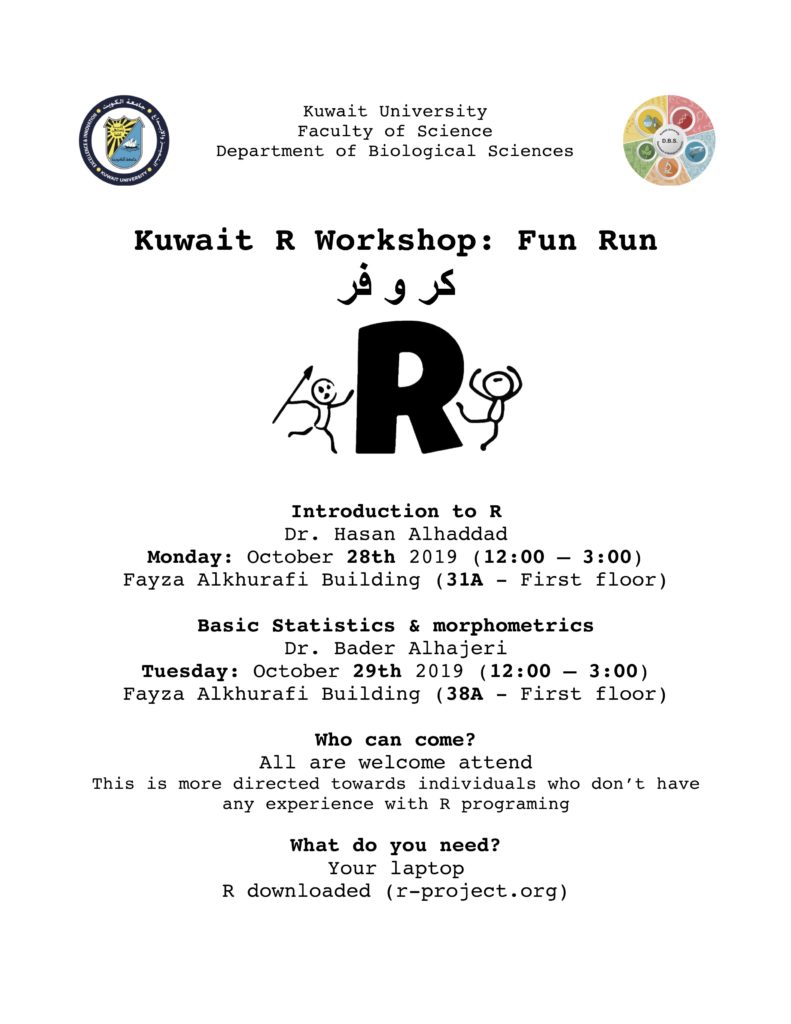

Two day R workshop at KU

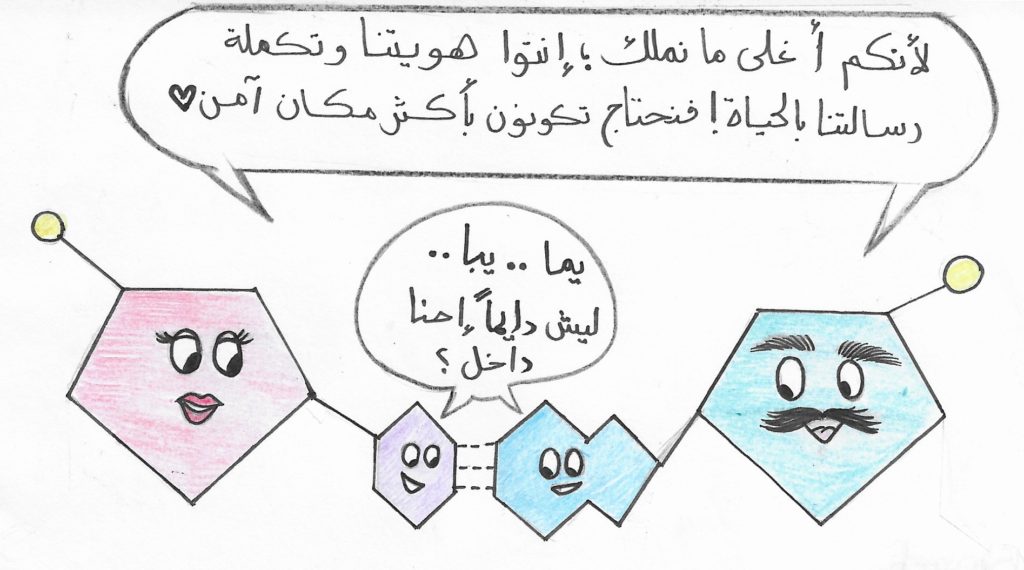

The sad story of two strands

Nice one by my 485 student: Hanan M. Ali

Intro. to Molecular biology (281)

Lecture 1: About the course (Readings: None, 281_Lec1)

Lecture 2: General introduction (Readings: Chapter 1, 281_Lec2)

Lecture 3: The identity and location of the genetic material (Readings: Chapter 2, 281_Lec3, Puzzle3)

Lecture 4: DNA: chemical composition (Readings: Chapter 2, 281_Lec4, Puzzle4)

Video: DNA building blocks

Lecture 5: DNA: the double helix structure (Readings: Chapter 2, 281_Lec5, Puzzle5)

Video: The DNA double helix discovery

Video: Pauling triplet helix

Video: James Watson – Basepairing

Video: Chargaff’s rule

Video: The double strands

Lecture 6: DNA: genome organization (Readings: Chapter 2, 11, 281_Lec6)

Video: DNA packaging – Basic

Video: DNA packaging – Advanced

Lecture 7: DNA: replication experiments (Readings: Chapter 10, 281_Lec7)

Video: DNA structure and replication

Lecture 8: Prokaryotic replication: elements (Readings: Chapter 10, 281_Lec8, Puzzle6)

Lecture 9: Prokaryotic replication: process (Readings: Chapter 10, 281_Lec9, Puzzle7)

Lecture 10: Eukaryotic and phage replication (Readings: Chapter 10, 281_Lec10, Puzzle8)

Video: DNA replication – Basic

Video: DNA replication – Advanced

Lecture 11: Transcription (Readings: Chapters 4, 5, & 6, 281_Lec11 , Puzzle9)

Lecture 12: Transcription in prokaryotes (Readings: Chapters 4, 5, & 6, 281_Lec12 , Puzzle10)

Lecture 13: Transcription in eukaryotes (Readings: Chapters 4, 5, & 6, 281_Lec13 , Puzzle11)

Video: Transcription – Basic

Video: Transcription – Advanced

Video: Eukaryotic mRNA splicing

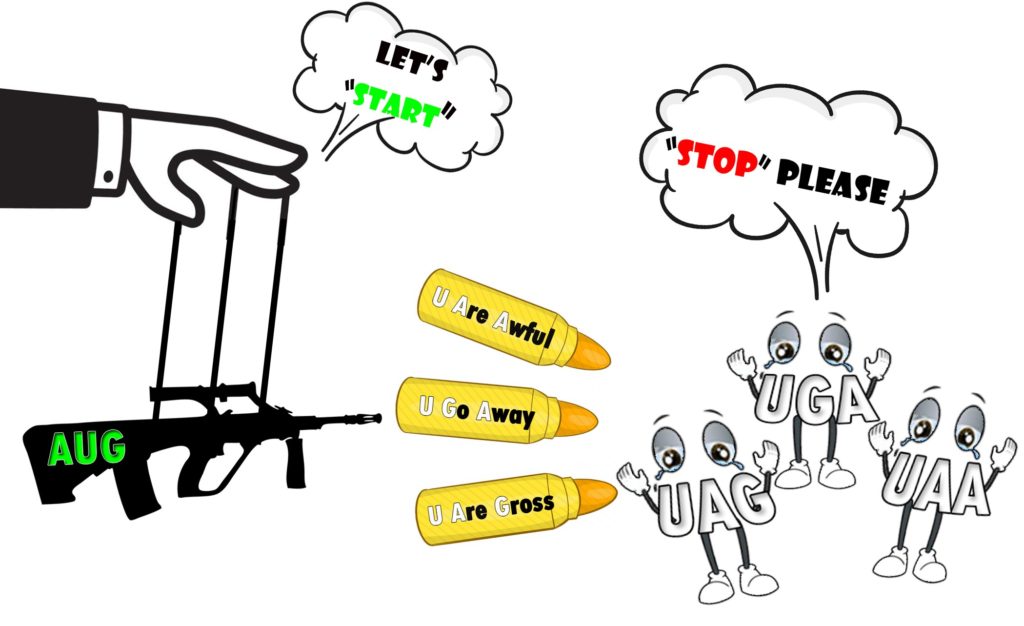

Lecture 14: The genetic code (Readings: Chapter 7, 281_Lec14 , Puzzle12)

Video: The Triplet Code

Lecture 15: Amino acids and proteins (Readings: Chapters 7 & 8, 281_Lec15 , Puzzle13)

Lecture 16: Translation: tRNA and rRNA (Readings: Chapters 5, 6, 7, & 8, 281_Lec16)

Lecture 17: Translation in prokaryotes (Readings: Chapters 7 & 8, 281_Lec17)

Lecture 18: Translation in eukaryotes (Readings: Chapters 7 & 8, 281_Lec18)

Video: Translation – Basic

Video: Translation – Advanced

Lecture 19: Regulation of gene expression: Generalities (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec19)

Lecture 20: Lambda phage repressor (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec20)

Lecture 21: Prokaryotic regulation (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec21)

Lecture 22: Eukaryotic regulation (I) (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec22)

Lecture 23: Eukaryotic regulation (II) (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec23)

Lecture 24: Eukaryotic regulation (III) (Readings: Chapter 9, 281_Lec24)

Lecture 25: DNA mutation (Readings: Chapter 16, 281_Lec25)

Video: The Fly Room

Movie: Mutation – The science of survival

Lecture 26: Point mutations (Readings: Chapter 16, 281_Lec26)

Lecture 27: Chromosomal mutations (Readings: Chapter 16, 281_Lec27)

Lecture 28: Sources of mutations (Readings: Chapter 16, 281_Lec28)

Lecture 29: DNA repair (Readings: Chapter 16, 281_Lec29)

Extra material not needed for exams but interesting to know!

Extra lecture 1: ModelOrganisms, Puzzle1.

Fun reads: What are model organisms?

Extra lecture 2: MendelANDGenetics, Puzzle2.

Extra lecture 3: DNA_Extraction

Video: How to extract DNA from strawberries

Extra lecture 4: DNA_Quality_Quantity

Extra lecture 5: PCR_DNAsequencing

Video: Polymerase Chain Reaction

Video: Sanger Sequencing

Video: PCR song

Video: Bio Rad GTCA song

Figures, photos, and graphs in my lectures are collected using google searches. I do not claim to have personally produced the material (except for some). I do cite only articles or books used. I thank all owners of the visual aid that I use and apologize for not citing each individual item. If anybody finds the inclusion of their material in my lectures a violation of their copy rights, please contact me via email.

UC Davis visit – 2019

January 9th 2019

It was a joy to return to my Ph.D. school (University of California, Davis) as the first destination of my one-year academic leave from Kuwait University. Beside reviving the memories and feelings associated with the place, I was eager to meet friends, colleagues, and mentors. I stayed, sadly, for only one day but had a chance to walk around the main campus and meet people despite the rainy weather.

For lunch, I was invited by the Grahns (Robert and Jennifer Grahn) to eat at Sophia’s. It is the best Thai restaurant in Davis, in my opinion. The lunch special of shrimp curry hasn’t changed over the years and my taste buds haven’t forgotten the delicious flavors. Rob and Jen Grahn are a couple of my dearest friends in Davis. I have shared the office with Dr. Robert Grahn throughout my Ph.D. years and shared much of my general and scientific thoughts as well as my feelings and frustrations. It was unusual for me and for them that our lunch extended for nearly two hours but I enjoyed every second of it and I hope they did.

Although not sure that walking would assist in the digestion of my tasty lunch, I walked around the nice small downtown of Davis and to my surprise I saw the Framers Market, which takes place Wednesday afternoon and Saturday morning of every week. The Farmers Market was one of the frequently visited locations of my family where we can try and buy different food items in addition to fruits and vegetables. My son, Ali, also has enjoyed the playgrounds and the company of other kids. On my way to the main campus, I passed by the 3rd and U Cafe where I used to join REHAB journal club on Fridays afternoon for a free learning experience.

A visit to UCD always starts with the Memorial Union. The place has changed a little since my graduation with more spacious foodcourts and a newly renovated larger bookstore. Drowning in my memories, it was a challenge for me to avoid all the bikers on campus. Davis is known to be the bicycle capital city in the United States and the campus is almost car free on its internal roads. Everyone rides a bike at UCD including faculty and if one decides to walk instead, a class or a meeting will definitely be missed. I remember re-learning how to ride a bike when I first joined the Ph.D. program of the Genetics Graduate Group (now known as the Integrative Genetics and Genomics – IGG – Graduate Group). When you are in Davis, do what Davisians do and ride a bike.

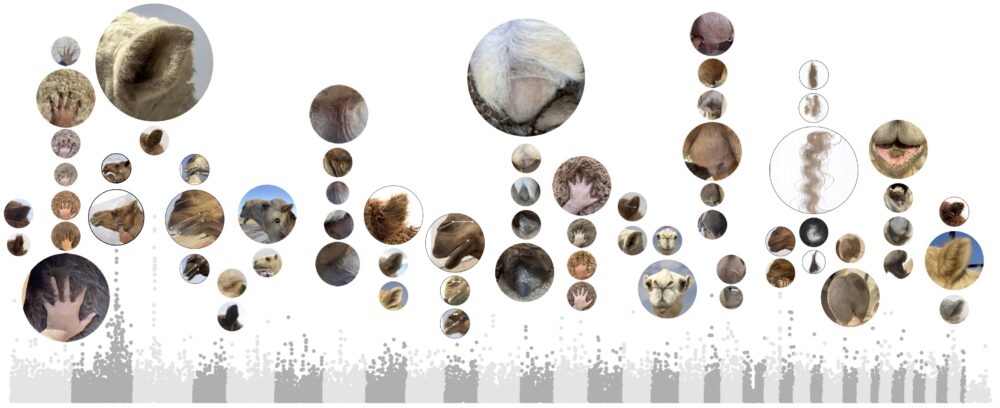

I walked my way to the office of my dissertation committee member and mentor, Jeffery Ross-Ibarra, at Robbins Hall. Jeff, as we call him, has been an inspiration for me as a scientist. He is a population geneticist and in love with studying corn. He taught me population genetics and was one of the many reasons why I love the topic. Also, He has been my inspiration to establish a journal club at Kuwait University (EHRAB) based on his entertaining and intellectually valuable REHAB. Two things stand out as the most memorable lessons that I learned from Jeff. The first lesson was scientific humility. I learned that by his ungarnished comments and questions, which were at the time quite hurtful but much needed on the long run and for a true scientific maturity. The second lesson was to be in love with the organism one studies. I still remember vividly my last conversation with him before my return to Kuwait after my graduation. He asked me “why camels?” His question was in reference to a statement that I made during my exist seminar that I am interested in studying camels when I return home. The first answer that came to my mind was “the camel has waited a long time for me to study it”. Of course my answer wasn’t along the lines of the first lesson that he taught me, humility, but it was may be a reflection of my determination and passion to study the camel and just like his passion to study corn. Without any prior appointment, I walked into Jeff’s office to see him standing in a chair-less room. Yes, he has a standing desk with two large computer screens. He told me that this was his treat for becoming a full professor. Nothing in the office changed. The nice vertical chalk-board is still in the same location and the corn samples and photos decorate the office elegantly. We chatted for about half an hour before I handed him a little gift from my camel lab. The gift was T-shirts and keychains/car mirror hanging accessory with a camel design.

From Robbins Hall I walked to the haunted building (a claim or a joke) Storer Hall where the office of my other dissertation committee member and my dear mentor, Bruce Rannala, resides. I knew before my arrival that Dr. Rannala would be in town. However, I wanted to walk to his office just like I used to when I was a student. Bruce, as he likes me to call him, has taught me statistics and was the first to introduce me to R programming. I still remember setting behind my friend Carolyn Yrigollen and leaning to the right wall of the classroom. When Bruce plotted a histogram using R, my first question was “is it possible to change the colors?”. He smiled and replied that a lot of things can be modified. I laugh when I remember this incident because for all the statistics that he was introducing to us, my only question was to the plotting, much to my love and fascination with visualization.

At about 4 o’clock, I drove to UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory (VGL). I had an appointment with my friend Rob (Robert Grahn) to meet old friends at the testing lab, to get introduced to the director (Dr. Rebecca Bellone), and to get a quick tour to the facilities, and equipments of the lab. I was familiar with the lab in general when I did the genotyping and sequencing aspects of my Ph.D. projects using their machines. Beside all the new machines and the automated systems for DNA extraction etc., I was particularly amazed by the number of samples that the lab houses and the way these samples are organized. Thousand and thousands of biological samples are stored from several species. I discussed the setup of my camel biobank (Cdrom Archive) with Rob who provided me with valuable suggestions and recommendations. I hope that my visit to the VGL puts the seeds for future camel specific collaborations.